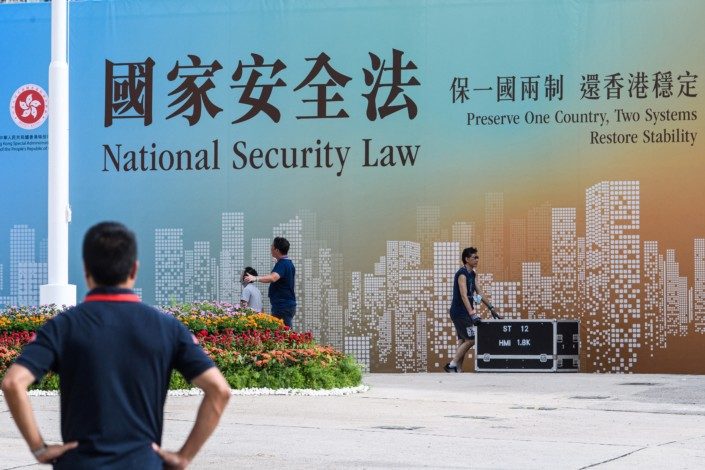

The enactment by the Chinese regime of the National Security Law (NSL) in 2020 marked a turning point for freedoms in Hong Kong. The city’s justicial system, once based on the Rule of Law, started using the NSL’s vague and all-encompassing provisions as a tool against critical voices. In this first article of a four-part series, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) along with expert Josephine K. examine the provisions of the NSL and how they pose a threat to press freedom.

On 30 June 2020, the central government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing promulgated with immediate effect the National Security Law to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). This law has brought tremendous changes to the legal system in Hong Kong as for the first time its enforcement does not fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the HKSAR but also under the Office for Safeguarding National Security, directly managed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

The law introduced four new types of offences: “secession,” “subversion,” “collusion with a foreign country or external elements,” and “terrorism activities.” The provisions on these offences are purposefully vague and broadly drafted, leaving government and security officers free to create their own definitions of “threats” to national security. A large number of international organisations, governments, human rights groups and legal associations warned of the risks of misuse and rights abuses of the law in the name of national security.

Provisions contravening press freedom

- Unchecked oversight of journalists. Article 54 requires authorities to “take necessary measures to strengthen the management of and services for (…) news agencies of foreign countries.” This could lead to extreme vetting of foreign journalists and increased visa rejections: in the past four years, many journalists have already reported being followed from their homes in the course of their duties. Security officers are also increasingly relying on “lawfare” tactics (the strategic use of legal proceedings) to hinder journalistic work, by charging journalists with obstructing police officers, accessing databases “unlawfully” and other padded charges.

- Government can instrumentalise the media to promote its policies. Article 10 requires the Hong Kong government “through the media (…) to raise the awareness of Hong Kong residents of national security and of the obligation to abide by the law.” State media outlets that produce pro-Beijing propaganda already financially benefit from the government’s “awareness campaigns,” while independent media often face allegations of “promoting” anti-government views for publishing a diversity of opinion on the new security laws or mere criticism of government policies. The resulting inability of the media to report freely and fairly on matters concerning governance strikes a hard blow against the role of the media as a mechanism to gauge government accountability and violations of basic rights.

- Government control on the public debate. Article 9 stipulates that the Hong Kong government “shall take necessary measures to strengthen public communication, guidance, supervision and regulation over matters concerning national security, including those relating to (…) the media.” The lack of clear legal consequences regarding regulation paves the way for the government to interpret the law without transparency or scrutiny and de facto strengthen its control over the media.

Provisions facilitating abusive prosecution

- The NSL allows the prosecution of journalists based outside Hong Kong. Article 38 stated that the NSL “shall apply to offences under this Law committed against the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region from outside the Region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the Region.” This means that journalists who have published critical coverage of the authorities or the Chinese communist party (CCP) from other countries can be targeted by warrants and be arrested upon entering Hong Kong. The broad police interpretation of what amounts to an NSL offence applies to almost anything, from songs, books, art, slogans, chants, to films and reporting.

- Police can search journalists without a warrant. Article 43(1) grants law enforcement authorities the “search of premises, vehicles, vessels, aircraft and other relevant places and electronic devices that may contain evidence of an offence.” Therefore, the police no longer require warrants or judicial oversight to enter premises or seize property, which can later be used legally by the prosecutor to build charges against the defendants in national security cases. Under common law, “journalists materials” were protected in the interest of press freedom, and the seizure of property was reserved for the most serious criminal offences and required judicial oversight. Media outlets can now be shuttered, their assets frozen and their electronic devices seized from the moment the police identify a potential breach of the national security law.

- State security officers (mainland police) have full authority and immunity from Hong Kong laws. The same article grants, “when handling cases concerning offence endangering national security, the department for safeguarding national security of the Police Force of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region [to] take measures (…) in investigating serious crimes,” without citing any judicial oversight nor legal consequences contrary to the fundamental principle of a Rule of Law jurisdiction that no individual is above the law. This creates an environment where journalists cannot rely on fundamental rights such as privacy, freedom from arbitrary detention or freedom of expression to defend their professional work.

Provisions facilitating abusive detention and sentencing

- Bail may be denied arbitrarily. Article 42 states that “no bail shall be granted to a criminal suspect or defendant unless the judge has sufficient grounds for believing that the criminal suspect or defendant will not continue to commit acts endangering national security.” As at the date of publication, almost 80% of individuals arrested have not been granted bail, and remain imprisoned until their trial, contrary to the presumption of bail that is the norm in the common law system practised in Hong Kong. In one famous case, the individual was denied on the basis of having given interviews to international media outlets.

- Trials may be carried out in secret. Article 41 stipulates that “when circumstances arise such as the trial involving State secrets or public order, all or part of the trial shall be closed to the media and the public,” in stark contrast from the principle of open justice that had been the hallmark of Hong Kong courts. Although this provision has not yet been applied in Hong Kong, the absence of any definition of “state secret” leaves journalists in particular peril, unable to gauge whether materials provided by sources in the context of their work would later be deemed as such.

- People arrested in Hong Kong may be transported to mainland China for trial. Article 55 grants “the Office for Safeguarding National Security of the Central People’s Government [the right to] exercise jurisdiction over a case,” under which they would be free to move the trial to mainland China. Like the former provision, no individual charged with an NSL offence in Hong Kong has yet to be tried in the Mainland. But the threat of being subjected to the criminal justice regime of the PRC, which still imposes the death penalty for an array of offences related to national and public security, and where reports of torture, withholding of legal representation and lengthy pre-tiral detentions are the norm, undoubtedly contributes to a climate of fear and self-censorship within the media in Hong Kong.

- Charges brought under the NSL cannot be challenged in court. Article 14 makes the precision that “no institution, organisation or individual in the Region shall interfere with the work of the Committee [to Safeguarding National Security]. (…). Decisions made by the Committee shall not be amenable to judicial review.” A judicial review empowers the courts to review the lawfulness of decisions of public bodies, such as the government and the police and weigh whether their actions are disproportionate in their impact on journalists’ rights and freedoms. Removing this possibility thus exposes journalists to enhanced risks and prevents the media from a potential key defence against legislation excessively eroding freedom in the name of national security.

Josephine K. is a pseudonym as the author wishes to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

→ Read Part 2: The Safeguarding National Security Ordinance (“Article 23”)

→ Read Part 3: Sedition laws

→ Read Part 4: Limited access to information