The recent resurrection by the Hong Kong government of the colonial-era Sedition Ordinance, combined with the provisions on seditious material of the newly adopted Safeguarding National Security Ordinance (SNSO), bring unprecedented threats to journalists reporting on Hong Kong. In this third article of a four-part series, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) along with expert Josephine K., examine the provisions of these laws on sedition and the threats they pose to press freedom.

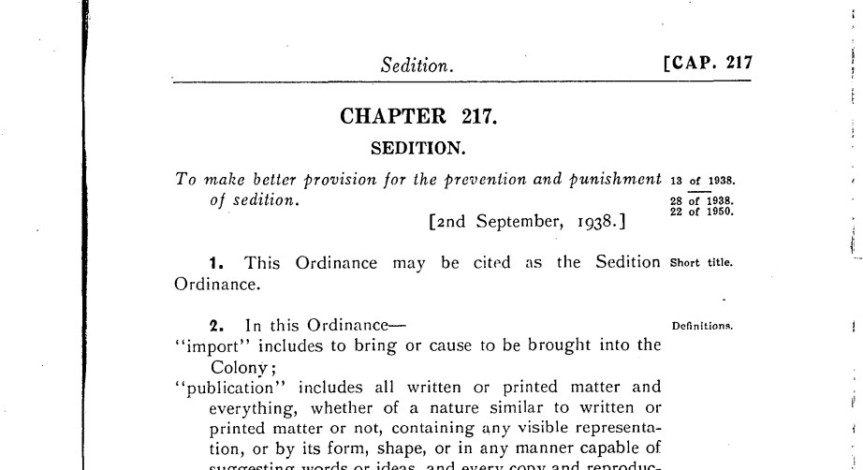

Hong Kong has had a Sedition Ordinance criminalising sedition, the act of inciting rebellion against the government, from its time as a British colony. However, it had been abandoned for over 50 years due to its incompatibility with fundamental rights and freedoms in Common Law jurisdictions globally.

This law was resuscitated by the government starting in December 2021 and was immediately used against journalists and critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The law covers seditious acts, words/utterances, publications and import of seditious materials. Additionally, the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance (SNSO), commonly called “Article 23,” adopted in March 2024, greatly expands the definition of sedition to encompass previously legal forms of anti-China critique and expression, and imposes harsher punishments.

Contravening press freedom

- Judicial overreach and declaring factual reporting as false. In the first legal case against a newspaper for sedition in nearly half a century under the Sedition Ordinance, the judge declared factual information in the reporting as being “false,” and therefore “seditious.” This ruling means any other journalists who reported on the same events were also marked as seditious.

- Courts can declare a publication “seditious” over very little. Under the SNSO Part 3.4, it is an offence to produce or possess material like video and written reporting that is made with “seditious intent” Seditious intention is defined as “intending to cause hatred, contempt or ‘disaffection’ towards the government or between classes;” or “intending to alter the political, constitutional or legal order by unlawful means.” These vague definitions have been used by the prosecution to claim publications incited all sorts of things, including just general widespread discontent.

- No need to prove “real risk” to national security. According to the SNSO Part 3.4, once the court has deemed a publication “with seditious intent,” it does not matter if the material poses no actual threat to national security or deliberate intention to incite public disorder, the writer can be prosecuted. This means the common practice of stating within an article or an oped that it is not intended to incite the reader to action, will not protect the journalist.

Facilitating abusive prosecution

- Prosecution of journalists based outside of Hong Kong. For offences related to sedition, the SNSO states that an offence made anywhere in the world falls under its jurisdiction if consequence occurs in Hong Kong. However, unlike the National Security Law (NSL), this reach is limited to Hong Kong residents and companies operating or registered in Hong Kong. This means local journalists, and foreign journalists with permanent residency, can be prosecuted even if they were working in another country.

- Hong Kong authorities’ jurisdiction over any critical material. Journalists who are not based in Hong Kong, nor have even been to the city, but have published works critical of the regime, can have warrants issued for their arrest. The broad police interpretation of what amounts to a seditious offence applies to almost anything, from songs, books, art, slogans, chants, to films and reporting.

- Extended detention time. Under the Sedition Ordinance, the maximum penalty for offenders was 2 years. The SNSO increases the tariffs substantially, with offenders now liable on conviction to imprisonment for 7 years. Where the court determines that the seditious materials have been produced in collusion with “external forces,” the imprisonment is raised to 10 years on conviction.

Facilitating abusive detention and sentencing

- Restrictions on legal representation. Part 7.1.2 of the SNSO grants the courts the ability to restrict access to a journalist’s lawyer of choice if police officials request it before the accused is charged. i.e. it can be made at any point during the 16 days of extended detention an accused may now face under the new legislation.

- Court backlogs and reversed bail presumption. Sedition offences are classified as “national security offences,” so the accused are held in prison unless they can prove to be of no harm to the community nor to the trial to be released on bail. It also means the sedition charges are tried in the District and High Courts, where severe backlogs mean it can take years to get to trial for accused individuals.

- Expansion of the range of penalties. Journalists convicted of “national security offences” can have their pensions or contract gratuities cancelled or reduced (Part 9.5 and 9.7). Passports can be cancelled without any opportunity to appeal. And the usual right to remission of sentence (i.e. having a sentence reduced for good-behaviour), can be denied at the court’s discretion (Part 9.14).

Josephine K. is a pseudonym as the author wishes to remain anonymous for safety reasons.

← Read Part 1: The National Security Law

← Read Part 2: The Safeguarding National Security Ordinance (“Article 23”)

→ Read Part 4: Limited access to information