Authoritarian countries are unfriendly environments for journalists to work in. In this first article of a two-part series, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) works with media law expert, Josephine K., to lay out the legal hurdles often faced by journalists in authoritarian regimes.

Authoritarian regimes remain in power partially by controlling information. Journalists, who seek to uncover and distribute information, usually find themselves the victim of vague and harshly enforced laws that restrict their free speech, ability to travel, or even lead to their arrest. Entering a repressive regime without proper risk analysis and legal support is ill-advised, and while the exact laws vary from place to place, there are some common risks all journalists should be aware of. In this first article of a two-part series, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) and media law expert Josephine K. examine how authoritarian regimes use regulations to restrict and deter journalists.

Immigration laws: restricting lawful presence in a country

In most cases, journalists are legally required to declare themselves at immigration. Immigration laws can then be abused by regimes to restrict journalists’ ability to enter the country, and move about it freely.

- Denial of entry can happen right at the border if a country so chooses, with no requirement to provide a reason.

- Unlawful employment can be leveraged against journalists reporting in countries where free speech and free press are restricted, and can result in arrest or deportation.

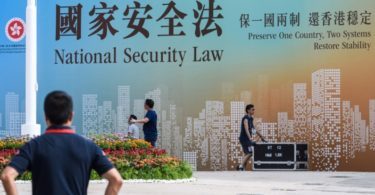

National security laws: declaring journalists a serious threat

One of the biggest risks a journalist faces is being declared a threat to national security. National security laws are extremely severe, and also often vague, repressive, and all-encompassing. In some cases, these laws can even be applied to a journalist’s previous work published in another country.

- Vague definitions mean a journalist can be arrested for something as nebulous as “external interference,” or “exposing state secrets” – the exact definitions of which are so blurry that even local lawyers are unable to keep up. They are often overarching: even basic economic and social data can be deemed a “state secret.”

- Seemingly minor offences like the use of non “state-approved” terminology or slogans, or the possession of historical materials now deemed seditious by new laws can fall under threats to national security, and allow a journalist to be targeted for arrest.

Non-media specific laws: restrictions on free speech

These laws represent a powerful weapon in the arsenal of moneyed regimes, state actors and individuals, as they can lead to either criminal (imprisonment) or civil sanctions. Both journalists and non-journalists alike can be charged under these laws, the difference lies in the disproportionate and aggressive use of these tools to harass and intimidate journalists who report critically about the regime.

- Trespass laws can be invoked to remove journalists from a particular area.

- Sedition laws are often broadly interpreted to target any criticism of the government.

- Defamation laws can be used to target journalists reporting on an individual person, usually wealthy and powerful, if the subject considers the report slanderous or harmful to their reputation. Under international law it is generally accepted that public officials should not be afforded the protection of defamation laws, but under authoritarian regimes, where criticism of the powerful is restricted, they remain a significant threat.

- Blasphemy laws in highly religious countries can target any reporting deemed to have criticised or shown a lack of respect towards something considered sacred or infallible, including the government or leaders.

- Lèse-majesté laws are similar to blasphemy, but specifically criminalise reporting that criticises the monarch of a country.

Police power: impeding media with complete impunity

The police and other authority figures in authoritarian regimes can exercise unusual restrictions to hamper journalists’ work that have been coded into regulations.

- Restricted access to press conferences. Under regimes where free press and free speech are restricted, police often have broad powers to refuse independent, non-state-approved media’s access to press conferences, without having to give any legal explanation or reason why.

- No search warrants needed. In authoritarian regimes, mobile devices can often be searched at will, while there will likely be no protections for “journalistic material,” such as the names of sources or sensitive data, from police scrutiny.

- Impunity for police misconduct. Criticisms of police behaviour are generally not tolerated in authoritarian regimes, and restrictive tactics like those above will not be openly reported by the regime, nor called on for responsibility.

→ Read Part 2: Advice to journalists and newsrooms.

Josephine K. is a pseudonym as the author wishes to remain anonymous for safety reasons.