The encryption of information and communications online is essential for journalists to protect themselves and their sources. In this article, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) explains the different types of encryption and recommends tools to help journalists secure their data and communication.

Encryption is the process of converting the regular content (plaintext) of messages or communications into a form that is unreadable to outsiders (ciphertext). However, if encryption is effective at masking the content, it does not hide the users’ identities or other metadata such as time or location. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) describes commonly used encryption techniques at each step of a communication process.

Encryption at rest

“Encryption at rest” means encrypting a file, a folder or the entire hard drive of an electronic device. This type of local encryption makes the device and files unreadable to outsiders who do not have an encryption key or password. It is highly recommended for journalists to encrypt at least their files and folders containing sensitive information, if not the entire hard drive for increased safety.

“Encryption at rest” means encrypting a file, a folder or the entire hard drive of an electronic device. This type of local encryption makes the device and files unreadable to outsiders who do not have an encryption key or password. It is highly recommended for journalists to encrypt at least their files and folders containing sensitive information, if not the entire hard drive for increased safety.

“Encryption at rest” protects the information contained on a device from an attacker who has physical access to it, which is very useful in case a device is stolen or seized by the authorities. It also prevents malware and spyware attacks. However, this type of encryption does not protect any data when they transit from one user to another.

Apple’s FileVault, VeraCrypt, and NordLocker are convenient services for encrypting full disks or files.

Transport encryption

“Transport encryption” means the connection between users and servers is encrypted. It helps protect communications online against other users who have access to the same network. However, using transport encryption means that the message remains a plaintext, and therefore can be intercepted by others with access to the same server.

“Transport encryption” means the connection between users and servers is encrypted. It helps protect communications online against other users who have access to the same network. However, using transport encryption means that the message remains a plaintext, and therefore can be intercepted by others with access to the same server.

On the web, a website with “https” means that the site offers transport encryption. On an “http” website (without the “s”), all information is transmitted in plaintext and is therefore not secure during its transport. Only the website operator can implement transport encryption, and journalists may not have the choice but to browse on “http” websites that are less secure. However, major browsers now allow users to turn on “https-only mode” for secure browsing.

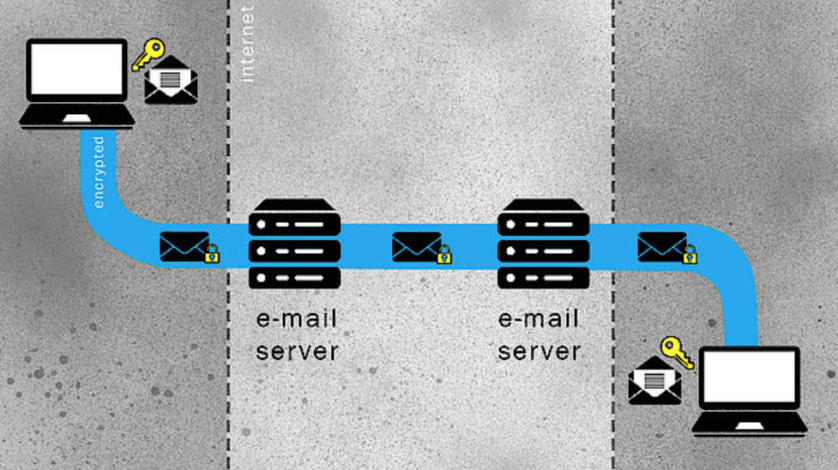

End-to-end encryption

“End-to-end” encryption is the best level of encryption commercially available, as it corresponds to the combination of transport at rest and transport encryption. This method makes communications decipherable only to the sender and the recipient. It is unreadable by the app server, email provider or government, even if they have access to the internet network. Journalists should only send sensitive messages and emails over end-to-end encrypted services.

“End-to-end” encryption is the best level of encryption commercially available, as it corresponds to the combination of transport at rest and transport encryption. This method makes communications decipherable only to the sender and the recipient. It is unreadable by the app server, email provider or government, even if they have access to the internet network. Journalists should only send sensitive messages and emails over end-to-end encrypted services.

Recommended end-to-end encryption tools

Email: The most common way to enable end-to-end encryption for emails is by using the programme OpenPGP, which has remained a standard service for encrypting emails for decades. Journalists are also encouraged to directly use email services which employ end-to-end encryption as a default setting, including Tutanota and ProtonMail — which allows users to employ a “self-destruct” setting and encrypt messages to non-ProtonMail accounts with a password.

Messaging apps: When communicating with sources, journalists should only use end-to-end encrypted messaging apps such as Signal and Telegram. While WhatsApp uses end-to-end encryption, it is not recommended for sensitive topics as it recently increased its metadata collection and made them accessible to Facebook, its parent company.

Test your knowledge about encryption here.